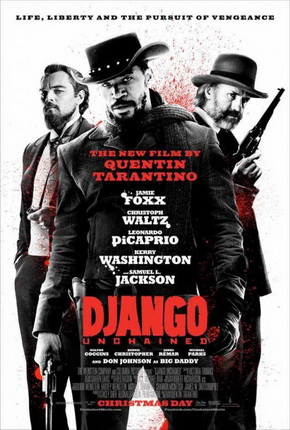

Tarantino’s latest work, Django Unchained is a hell of a ride, great in all the ways you’d expect from a Tarantino movie – violent, stylish, vivid and often comedic in its outrageousness If you haven’t see it, it’s set in antebellum America and concerns itself with freed slave, Django (Jamie Foxx), attempting to become reunited with his missing wife who just so happens to be owned by a frightening plantation owner with a fondness for popular science and racialist anthropology. While I personally prefer Inglorious Basterds, Django Unchained is still worthy film. Hell, it even got best screenplay at the 85th Academy Awards.

* Some minor spoilers for Django Unchained – This post assumes some familiarity with the movie *

One idea the movie has resurrected is the pseudo-science called phrenology – a populist science that at certain periods of the 19th century dominated scientific and medical discourse. Reviews and message boards all over the Internet have recoiled somewhat in horror that a science that justified racial discrimination and enslavement was ever allowed to exist in the history of ideas.

Here’s part of the scene that has sparked so much discussion. This is actually the end of the scene but Leonardo DiCaprio’s character Calvin Candie does mention looking at three dimples on the inside of the head of his slave Broomhilde. If you’ve seen the movie, you’ll know what I’m talking about.

Phrenology has an enduring interest to me. I just so happened to write a detailed thesis on the processes of historical change amongst medical classes in 19th century America using phrenology as the lens by which to view this change. It was an interesting project of little practical application but when it popped up in Tarantino’s movie, I was drawn to make a comment on it’s portrayal and also comment further on the ideas history.

***

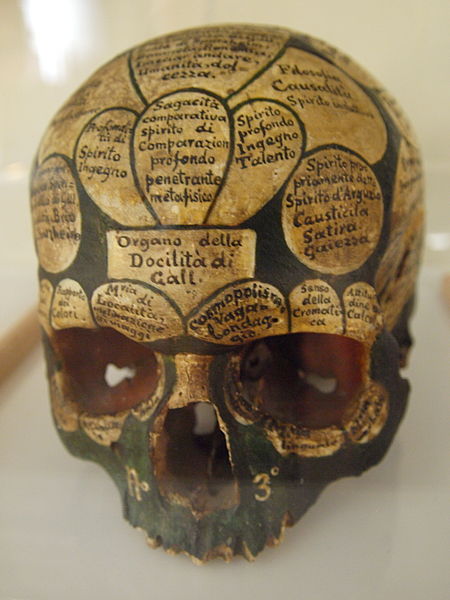

If you don’t know what I’m talking about – permit me a brief explanation. Franz Joseph Gall, an Austrian doctor, came up with the idea of ‘craniology’ (later termed ‘phrenology’ by Gall’s assistant Johann Spurzheim) after examining countless cadavers and in particular the shape and form of their heads. Gall demarcated the human skull into 27 sections, each corresponding to a behavioural characteristic that he called ‘organs’ (the number of ‘organs’ would later vary with various practitioners, doctors and scientists inventing many more). You may have seen a phrenological bust before – they’re a fairly common kitsch item. I have one myself!

Gall and Spurzheim theorised that through exercising these ‘organs’ one could modify their external behaviour. Heads were ‘read’ by examining bumps on the outside of the skull, and by knowing your moral or character flaws, one could aim for a more moral or ‘good’ existence and change ones behaviour. Thus, sin or morality, in the eyes of phrenologists, became a treatable condition. The idea spread like wildfire amongst the elite of Western Europe and The British Isles, and phrenological societies became popular pastime amongst scientific, medical, legal and even religious classes.

It found a particular fertile home in antebellum America – where fatalism and ‘manifest destiny’ and the idea that shaping ones future was within the grasp of the common man defined frontier America. Entrepreneurial characters like Orson and Lorenzo Fowler established business as roaming ‘practical’ phrenologists, who would read heads for a fee, and allow one to gain access to a ‘science’ that would solve moral and social dilemmas without having to rely on God’s good graces. It was these reasons that phrenology was often referred to as the ‘science of man’.

The full story of phrenology is a lot more detailed and complicated than I’ve explained here, but I think I laid out the requisite amount of information to launch into my next point.

***

Was phrenology an example scientific racism? I would argue yes and no. Its initial intention seems to revolve around curing moral problems and the vices of the state of nature. Phrenology was popular because people were aware of behavioural defects not only amongst themselves as individuals, but also within wider society. Things like crime and mental illness were all ‘phrenologised’ and people thought by having heads examined for behavioural issues, individuals could ‘become better’. Phrenology could be used to determine if an alleged criminal was actually predisposed to crime by the story his skull shape told. Think about how modern day courts use psychiatrists to determine the mental state of alleged criminals and you’ll get a good idea of the concept.

However, phrenology did dwell on ideas that could only be considered racist by today’s standards. Historically, those racialist tendencies can be traced back to ideas pedaled by the likes of Samuel Morton’s. In Morton’s Crania America, he looked at the size and shape of skulls and estimate about brain cavity sizes amongst different races and used this as the basis of his idea of polygenism: that humans were fundamentally made up of a different species. Lorenzo Fowler, one of the most well-known 19th century practical phrenologists claimed that phrenology could account for variance in racial types, believing that American Indians and African-Americans had hereditary inclinations to a certain set of phrenological ‘organs’.

However, there were those boffins of the time with a prevailing interest in phrenology repeatedly who couldn’t see a discernible difference between the size of skull types from all races. What was interesting about the time period was that phrenologists, while believing in racial inferiority, touted phrenology as a method of overcoming perceived racial disadvantages in addition to being a science to solve moral inferiority – essentially that African-Americans and American-Indians could access phrenology to become as ‘moral’ and ‘good’ as Caucasians.

Phrenology was certainly a good example of a wrong idea, something that didn’t stand up to the empirical scrutiny and now rightly debunked as pseudoscience. It flourished in an era of extremely racist people. I’m not surprised that the character of Candie in Django Unchained was so interested in phrenology and it would not have been unusual for these ideas to be popular in antebellum America. The thing is the ideas of phrenology were not explicitly set out to classify different racial types, rather instead attempted to solve problems of morality and sin without having to rely on an outside deity. However, it does seem that the idea was pounce upon with those people who were inherently racist or had a vested interest in giving ‘scientific’ justification for dominating and enslaving others.

***

One final thought in an otherwise already bloated essay. Did Tarantino portray phrenology correctly?

In the film, Calvin Candie talks about how smacking open a black slaves skull with a hammer to examine the inner contours of the skull and correspond them to character or racial traits. Apparently Tarantino got this idea from a book published in the early 20th century called ‘Negro, Beast of Man’, but by that stage phrenology had long since been debunked and was the province of only very deluded non-scientific people.

The way to ‘do’ phrenology relied on the external shape of the skull. Bumps and contours were examined by phrenologists, who might be a doctor or scientist or a ‘vulgar, practical’ phrenologists (the type who traveled the country performing at carnivals and so forth) . However, in Django Unchained, the character of Calvin Candie talks about the inner contours of the skull. This doesn’t really make sense even in the minds of 19th cenutry practitioners – if phrenology was practised in the way suggested by Calvin Candie back in the 19th century, practical phrenologists (the types who went to carnivals or town fetes) wouldn’t have had a business. After all – they can’t very well go around smashing open peoples’ skulls to check for dimples and bumps.

My thoughts here is Tarantino simply portrayed phrenology this way for dramatic effect. The imagery of Candie smacking open someone’s skull to check for bumps is horrifying image. The historical reality this probably didn’t happen. This article by Professor Karen Johnson over at Polite and Society reminds us that Django is a fictional and dramatic movie and not a historical piece.

***

If you made it this far – thanks for allowing me to indulge in talking about phrenology and 19th century America. I guess if I was forced to conclude, I’d say that Tarantino’s Django Unchained used phrenology well for dramatic impact but perhaps misled audiences with regards to the ideas historical impact. Essentially, phrenology was initially thought of a science to solve moral problems rather than justify racial superiority, although there is no doubt it warped into this particularly as the 19th century went on. And Tarantino’s character Candie described the practice of ‘phrenologising’ someone incorrectly – it was the outside of the head that phrenologists look at – not the inside.

Keep in mind with the above, the history of phrenology is much more complex than the simplified version I’ve outlined above, but hopefully it gives you a basic grasp of the issues in regards to how they relate to Django Unchained. Above all, let’s not stop these things from ruining an otherwise excellent film!

- This is a good related read about Django Unchained at The Quietus – Django Fever: A Hidden History Of Django Unchained.

- The Guardian also have a nice feature exploring phrenology specifically – Django Unchained and the racist science of phrenology

- The New Yorker on the depiction of slavery in Django Unchained – Tarantino Unchained

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.